Yet in this baiting of our reading cues, we find that while good, Zafón's YA falls a grade just below the texture & completeness of his other The Cemetery of Forgotten Books trilogy. There's the same edgy anticipations, looming gothic structures, innocent characters threatened by past tragedies, and all the darkly delightful earmarks, but it's Zafón-lite. Still, Zafón-lite is better than most other authors on their most gravitas of writing days.

| [Slightly more defined import cover figure than on the U.S. version.] |

The Prince of Mist

From the author's opening note:

"I like to believe storytelling transcends age limitations, and I hope readers of my adult novels will be tempted to explore these stories of magic, mystery, and adventure."

A classic R.L. Stevenson thing to say, and entirely appropriate.

This first installment's nothing less than Bradberryesque, a childhood-that-never-was small town paene in the vein of Something Wicked This Way Comes, complete with an equivalent parallel to Mr. Dark, and as sinister a group as Darren Shan's Cirque Du Freak could muster. Like these other two, there are elements that are brutally adult, and like all great children's books, they strive to appeal to all ages so they can both awe the young with their dark wonder, and stand the weathering test of acidic maturity.

Zafón almost spares us the YA trope of orphans, but maintains one character, Roland, as having lost his parents to an accident. Beachcomber Roland befriends seaside town newcomer Max, and by association, his unignorable lovely sister Alicia, which of course makes for a strained relationship dynamic:

"Hey," Max hissed at him. "She's my sister, not a piece of cake. Okay?" [ch 6, p.65]

As the children's summertime unfolds, weird inexplicable events begin to happen in their old house with a mysterious past, and the search for answers begins.

When the novella progresses and we just begin to see the adversary, carnival leader Cain's powers are never really defined, and his threat becomes too powerful, and his villainous behaviour too Snidely Whiplash arch, with his motives far less clear than foreclosure or banging virginal Nell:

"In an infinite universe, there were too many things that escaped human understanding." [ch 12, p.147]

Unlike Zafón's The Angel's Game, where a loose magical realism and far more complete style frames the narrative, the above quote allows Cain a limitless supernatural might, which stretches credulity, and makes his lines feel more comic book caricature than realized literary character.

|

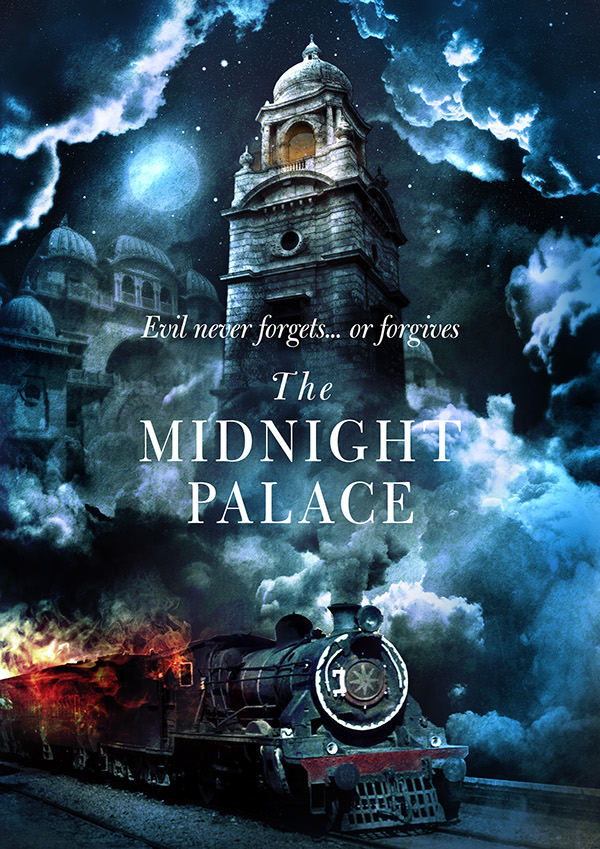

The Midnight Palace

An even more marked departure from Zafón's familiar home Barcelona, surprisingly set in a past exotic Calcutta, this middle book launches the reader into a vicious in media res beginning chase. This is an English imperial novella, but with some parallels of India pre-liberation to the author's native post-Spanish Civil War. The pacing's quickly constructed, and up & running from the get go.

Starring a cadre of precocious Indian children you so wished were your intellectually wisecracking friends, at childhood's end on the eve of their graduation from a Christian orphanage, we discover they also have in common The Chowbar Society: A secret clique mutually dedicated to aiding each other, meeting in a nearby abandoned house they've dubbed The Midnight Palace, where they sneak off to tell ghost stories, personal confessions, and problem solve. It is this altruistic society that runs up against hunter-villain Jawahal, a dark pyromancer, who, for unknown reasons, is after their new friend Sheere.

In contrast to the pacing, Zafón unfolds the mystery with tantalizing slowness, and the reader is compelled through urban Calcutta to follow these youths to a deadly and long hidden truth.

The Midnight Palace, a place plainly dilapidated with abandoned neglect by day, but is imbued with evocative magic for the teens by night, itself displays Zafón's love of architecture:

"The place exuded that aura of magic and dreams that rarely exists beyond the blurred memories of our early years." [p.79]

The celebratory ornaments of buildings easily slides into the spectrum of the sinister in many other of the book's settings, so the wonder is equally matched, and at times outdone, by the spooky.

Like Star Wars' prequel trilogy, the narrative arc becomes about the antagonist as its his slowly revealed history that frames the narrative and motivates the Chowbar Society's desperate investigations. This antagonist's similarities to the first book also place them as a shade too arch, more of a Freddy Kruger entity, nightmarish, complete with a boiler (for real). This final unveiling nearly undermines all the exotic delight and panoply of characters the book otherwise has. And in this strength alone, Zafón could easily write a series of Chowbar Society stories, the construct is so winning, but we only get this one.

The Watcher in the Shadows

Of the three, this mostly resembles his adult works, which makes sense as he wrote it last. Zafón again departs from his Catalanes setting into nearby Normandy, France.

With many similarities to Prince, we follow a family with even more unfortunate circumstances to a small coastal town where widow Simone takes a household managing post for an eccentric genius toymaker, as her children Irene & Dorian adjust to their new home nearby.

Zafón delivers yet another wonderful mansion setting full of spooky automata, but laced with pathos:

"As she listened to the toymaker’s words, Irene realised she would no longer be able to view Cravenmoore as the magnificent product of a boundless imagination, the ultimate expression of the genius that had created it. Having learned to recognise the emptiness of her own loss, she knew this place to be little more than the dark reflection of the solitude that had overwhelmed Lazarus during the past twenty years. Every piece of that marvellous world was a silent tear." [p.23]

And if you're reading Mists as we were for its connection to The Cemetery of Forgotten Books, Andreas Corelli gets mentioned in passing, and so the tie-in (two books later!) is finally revealed. Also the villain's nature more closely ties this third installment in with Mist but less so with Midnight.

As far as connections that make this a trilogy, the ability to "shadow" in the Zafóniverse results in similar adversaries in all three, and the Faustian bargaining exhibited in The Angel's Game strikes the same chord through these books. In both trilogies Zafón persistently explores the sins-of-the-father, and the quest of the innocent to both uncover & escape the horrors of generations past. The cost of doing so is always that same innocence.

| [Zafón is the man!] |

Not as complex, not as ornate, but one can see the formative merits as Zafón cuts his chops in this earlier material and the building of the writing to come. The comparison of earlier to later books is perhaps unfair as these are intended for a younger audience, but given the aforementioned fishhook, adults will be compelled to pick them up just to see if the later story seeds from The Mists Trilogy. Yet one can easily imagine that if Zafón had incubated these awhile longer & re-drafted, they very well might have had the same impact as his adult literature.

# # #

While a mostly happy bookstore fixture for over two decades, Guillermo Maytorena IV is currently willing to entertain your serious proposals for employment as a literary/cinema critic, goth journalist, castellan, airship pilot/crewperson, investigative mythologist, or assisting in a craft brewery. Should you be connected to any of the above or equally interesting endeavours, do contact him via LinkedIn or G+.